On July 23, 2025, the ENTRE team recorded an oral history as part of our Boca Chica, Corazón Grande project. The project is “focused on collecting and documenting the history and geography of Boca Chica Beach,” taking the form of a “collaborative initiative” that “uses the power of memory, storytelling, and archiving to preserve and celebrate the cultural richness of our communities and land.” ENTRE Worker-Owner Monica Sosa served as director and oral historian, Jenny Alvarado of LOBA Productions was the director of photography or camera operator, I worked as production assistant, and Mary Helen Flores was our subject and Narrator; Worker-Owner C was recuperating from COVID, but they worked virtually as the producer.

Monica and C had previously met with Mary Helen in person and talked on the phone several times, discussing their hopes for the project and going over potential questions and topics beforehand. Taking this approach ensures a level of trust crucial to an oral history that is not always necessary or warranted in a typical journalistic interview. Mary Helen knew the types of questions Monica would ask her in the interview, and we all went into the recording session feeling at ease and ready to be open and vulnerable with each other.

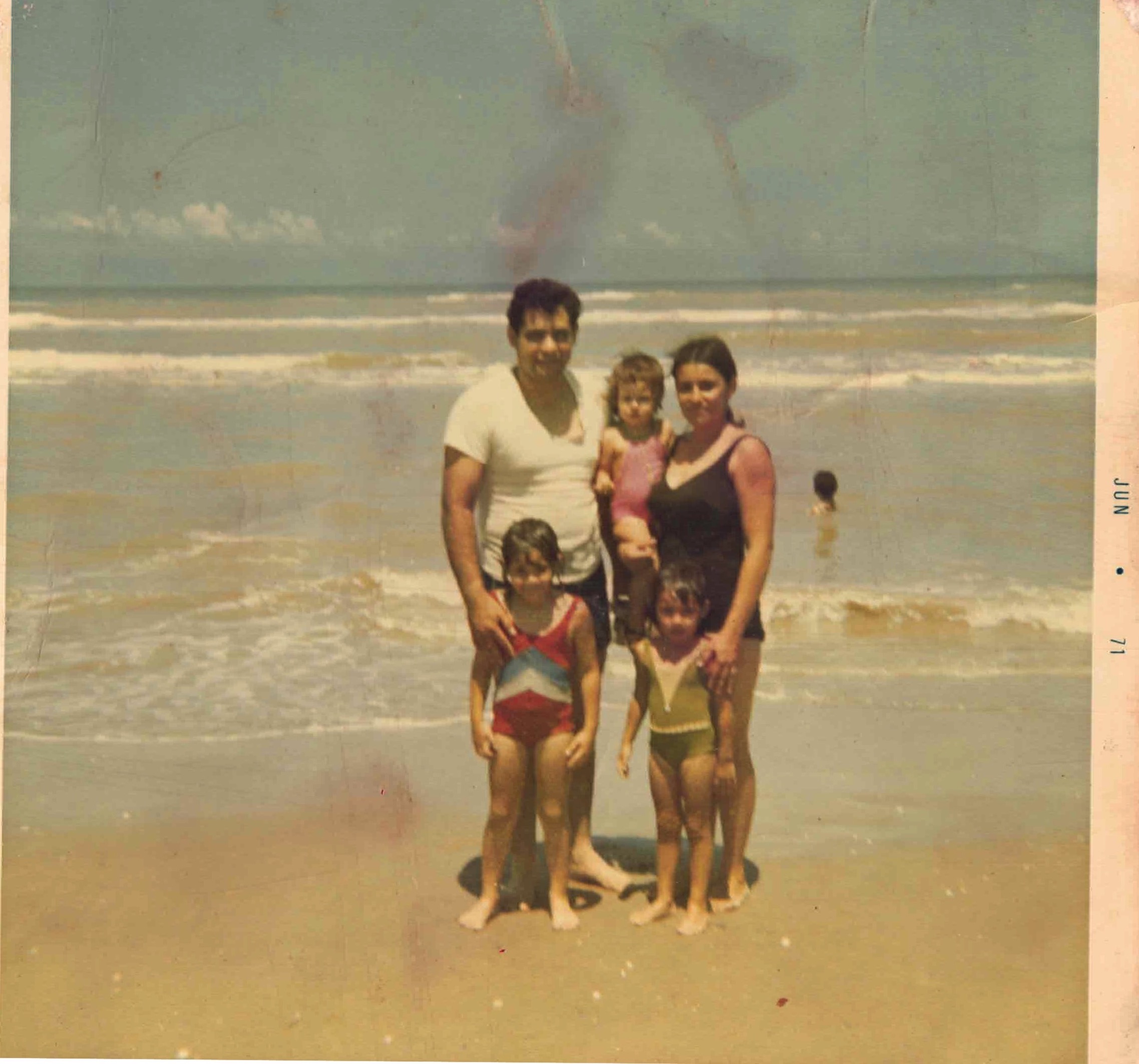

Mary Helen’s family has gone to Boca Chica throughout her life; in fact, some of her earliest memories are of her dad loading up his fishing supplies and making the drive out to the beach so early in the morning that it was still dark outside. She told us about how she used to be such a strong swimmer that she swam out past the second sand bar, how her relationship with the beach changed as she grew older but remained important, and how amazing the flights of the pelicans look over the course of the day. That compassion for the beach as a beautiful physical site and host of rich wildlife spurred her to learn about marine life in high school. She has been a strong proponent of protecting and saving the beach for decades, even prior to SpaceX’s move to the area. She talked about how difficult it is to even go to the beach anymore due to the construction and debris, and worries that her nephew’s son and others in his generation and those to come won’t even be able to enjoy the beach.

Oral histories are sometimes discounted because, at their core, they “are good at revealing the feelings and impressions about events, actions, and people from the interviewee’s perspective.” Throughout our interview with Mary Helen, you could see and hear the emotions she has felt throughout her life about the beach and various threats to it, especially from local politicians and SpaceX. However, just because “these interviews have a deeply personal meaning to the interviewee” doesn’t mean they’re not valid historical references. Most cultures came from a rich tradition of passing on stories via spoken word, and oral history was created from this common root. Like any historical record or document, oral histories can—and should—be fact checked to whatever degree possible, but they remain valid sources of historical record where there might be little to none, as “some historians argue that written records are good about telling what happened in the past, while oral testimony is best at telling how people felt about what happened.”

After hearing Mary Helen’s story, I certainly have a much greater sense of the havoc that SpaceX has wreaked on Boca Chica Beach from participating in this oral history project. When you look up the beach online, you get sparse information about the beach and landscape itself, and the picture on the Visit Brownsville webpage about the beach shows SpaceX property, not even the water, sand dunes, or wildlife that lives near and on the beach. There’s little information online about how Boca Chica Beach is a sacred site to the native Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe, “the site of [their] creation story”; in fact, there’s little information out there about how the Carrizo/Comecrudo were numerous along the Rio Grande Delta when the Spanish first came to these lands, about the origin of their name—Carrizo refers to the reeds or canes that they typically covered their houses in, Comecrudo means those who eat raw to harken to the partially raw state of their food, which was cooked in animal paunches—about how “regardless of the lack of culture and tribal understanding, of written historical data, the so called dependency factor, apparent genocide and Christian conversion, the Carrizo/Comecrudo still survived the occupation of their homelands and spiritual souls.” Without going to the beach or hearing from someone who has, you don’t know that there’s a sign referring to Boca Chica as a turtle habitat, with the threat of rockets and their debris looming over these creatures.

After visiting the beach twice myself, I saw both the stark, raw beauty of the land and the threats it faces. It put into perspective Mary Helen’s feelings about its importance to locals, and how that feels threatened as SpaceX ramps up its activity and the city of Starbase grows. I can’t wait to see how Boca Chica, Corazón Grande grows as a living, breathing documentation of a sacred site worthy of care, preservation, and enjoyment for generations to come, especially by Brownsville natives and visitors from the Valley and beyond. The production was hard, but these stories are so important to compile and share with the world. To quote the Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe, I hope this oral history and those to come “bring others to [the] existence” of Boca Chica Beach, “which never faded, just remained hidden.

Written by Linda Smith

ENTRE Archive Intern (Summer 2025)